J. Richard Steffy’s Lost Ship Model – By Loren Steffy

March 6, 2013 The letters nagged at me like a persistent hint from the past.

The letters nagged at me like a persistent hint from the past.

I’d first encountered them among my father’s papers as I researched my book, The Man Who Thought Like a Ship. They pertained to a ship model he’d built in the 1950s of an ancient Egyptian vessel. The model left home before I was born, and everyone, my father included, assumed it had been discarded long ago. I’d only ever seen it in pictures.

My father, J. Richard “Dick” Steffy, was a pioneer in nautical archaeology. He developed a method for rebuilding ships from their sunken hull fragments and proved those theories by rebuilding the 2,300-year-old Kyrenia Ship in Cyprus in the early 1970s. He helped found the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1985.

J. Richard Steffy with the Egyptian model soon after it was completed in 1963. He won Best of Show in the county hobby fair. (Photo courtesy of the Reading Eagle).

For the first 25 years of his working life, he was a small-town electrician in central Pennsylvania, and then, without even a bachelor’s degree himself, used his expertise in ship reconstruction to become a professor at Texas A&M University. Today, scores of his former students employ his methods worldwide.

The Egyptian model, though, hearkened to an earlier time, to the early years when my father still spent six days a week wiring factories and the wee hours of his nights building ship models in the basement.

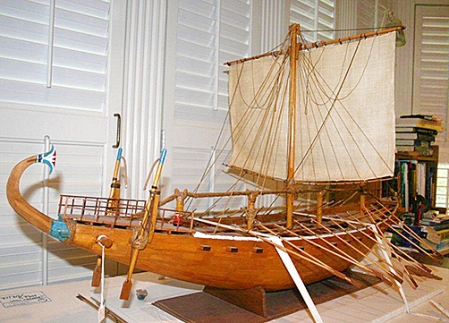

Using what scant research he could find at the time about Egyptian shipbuilding, he attempted to reproduce with his model the original construction techniques. Each hull plank was about an inch and a half long, reflecting the short trees that the Egyptians used in shipbuilding. They were painstaking edge-joined, and the entire hull retained its shape from tension applied by a rope truss that ran from stem to stern. The Egyptians used no keels or frames.

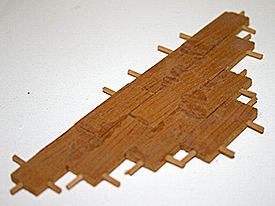

An example of the model’s joinery.

In all, the model had 2,000 pieces, and it took him more than 400 hours over 12 years to complete. As he built it, he began to lay the foundations of his new career, formulating the use of models in rebuilding sunken hulls.

In 1963, he arranged a meeting with George Bass, who had led the world’s first underwater archaeological dig off the coast of Turkey three years earlier. My father offered to build a model of a Byzantine wreck from the seventh century that Bass had uncovered. To seal the deal, to show his mettle as a modeler, he brought the Egyptian vessel with him to the meeting.

“I had no way of knowing how accurate it was or anything else,” Bass recalled. “It was the first time I’d ever looked at the model of an ancient ship. It wasn’t one of these slick yacht models.”

Nevertheless, Bass was thrilled with the idea of a Byzantine model, and this electrician seemed to know what he was doing. The two would begin a friendship and professional collaboration that would last the rest of their lives.

While my father would embark on one of the world’s more unusual career changes, the Egyptian model seemed to disappear.

No one, least of all my father, spent much time wondering what happened to it. He had little love for his models. Most weren’t built for aesthetics. He saw them as research tools that, once he had learned all he could from them, should be discarded. Because part of their lesson was to show how a ship broke apart when it sank, most didn’t last long. Only three others – including the one of the Byzantine wreck that he agreed to build for Bass – are known to have survived and are on display in museums in Cyprus, Turkey and South Carolina.

Perhaps that’s why I couldn’t get those letters out of my mind. Given the chance to find one of his long-lost works, I decided I had to know for sure what had become of the Egyptian ship. The letters provided a clue.

I got in touch with Cynthia Eiseman, a former student of Bass’s who’s been involved with nautical archaeology for decades. She wrote one of the letters in 1969, while working a summer job at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum. Her letter indicated my father had donated the Egyptian model to the museum, and she was asking what he wanted done with it.

The model soon after arriving at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum in 1965. Note the clay figures of the crew, which have since crumbled.

“It was a surprise to hear the model is still in existence as it was not built for display purposes and has led a hard life,” he wrote back. “I would like to see the model on my next trip to the museum to find out why it has not disintegrated because it is basically only held together by the pressure of its own gunwales.”

Eiseman, who still lives in Philadelphia, didn’t remember the exchange or the model, but she offered to help look for it.

A few days later, she called to say she’d found it. It had been sitting for years in the storeroom of the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia, which had been searching for a home for it.

The museum focuses on the maritime history of Philadelphia. Ancient Egyptian ships fall outside of its mandate, and the museum had “deaccessioned” the model in 1993. Since then, it remained in the a store room filled with shelves of ship models and seafaring artwork.

“Given that your dad never kept his models, it’s extraordinary that this one has survived,” Eiseman said.

Fortunately, the museum couldn’t bring itself to part with the ship.

“Museums sometimes have a hard time letting go,” Chief Curator Craig Bruns told me. “Nobody found a proper place for it until you asked. As a curator, I see it as a happy ending.”

Independence Seaport Museum Chief Curator Craig Bruns in the museum’s storeroom.

Last summer, I went to Philadelphia and drove the model to Texas, where it will but put on display in INA’s headquarters once a building renovation project is completed later this year.

Bruns provided letters from the museum’s files that filled in a few key details of the model’s history. My father wrote the museum in 1963 and offered to loan it the model, which he did in the summer of 1965.

While it didn’t fit with the museum’s mission, it was on display there for a time. Bruns gave me a plaque that had accompanied it and included the explanation: “While not a part of Delaware Valley history, it could be considered the `grandfather’ of all sea-going ships.”

It could also be considered the work that best represents my father’s transformation from hobbyist to ship expert.

The model remains in excellent condition. A few of the oars have fallen off and the crude figures my father fashioned to represent the crew have crumbled or broken away. The hull itself though, remains intact, still held to the proper curvature by the rope truss.

“It is an artifact of a discipline that he helped create,” INA President Deborah Carlson said. “As a teaching tool the model will be accessible to students and faculty leading seminars in ancient seafaring and ship construction technology.”

The hull was formed from one-and-half-inch pieces designed to recreate the short timbers used by Egyptian shipbuilders.

I wonder what my father, with his lack of sentiment for his creations, might say about that. He would be embarrassed by the model — there’s nothing that can be learned from it, he would say — yet if it benefited students, we would probably acquiesce to the display.

In the meantime, the Lost Ship Model waits to complete the last leg of its amazing journey. Sometimes, as I pass the room it’s in, I can’t help but stop there and peek inside its traveling crate. It’s as if my father’s dreams remain there, suspended in a time before they were fulfilled.

Nautical archaeology is now a recognized field of study, thanks to decades of effort by early pioneers like Bass and my father and the students they helped train. It is old enough that the field itself is developing its own history, a way for students who didn’t know the first generation to better understand how they developed their skills.

In a field that studies the past, the long-lost ship model offers a touchstone to its own unique history.

For more information about J. Richard Steffy see Loren Steffy’s book: The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

_______________________________________________

Loren Steffy is a columnist for the Houston Chronicle and the author of The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

* The opinions expressed by guest bloggers do not necessarily reflect those of the MUA, its staff, or its partner organizations.

What a great story! Thanks, Loren and Kurt, for making it available!

Just wow ……………. Loren and Kurt its unbelleaveable .. man … thanks for posting

Few include detail design and analysis of a ship model also delivers in axsys.

I was privileged to work with Dick Steffy on a number of projects in South Carolina, The Brown’s Ferry Vessel and the Cooper River Revolutionary Gunboat. He was a great guy, generous with his knowledge and support to a then student in the field. Thanks for this great piece!