The letters nagged at me like a persistent hint from the past.

The letters nagged at me like a persistent hint from the past.

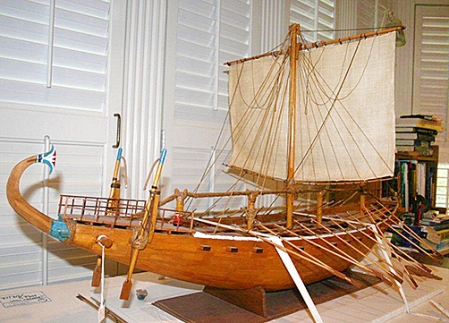

I’d first encountered them among my father’s papers as I researched my book, The Man Who Thought Like a Ship. They pertained to a ship model he’d built in the 1950s of an ancient Egyptian vessel. The model left home before I was born, and everyone, my father included, assumed it had been discarded long ago. I’d only ever seen it in pictures.

My father, J. Richard “Dick” Steffy, was a pioneer in nautical archaeology. He developed a method for rebuilding ships from their sunken hull fragments and proved those theories by rebuilding the 2,300-year-old Kyrenia Ship in Cyprus in the early 1970s. He helped found the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1985.

J. Richard Steffy with the Egyptian model soon after it was completed in 1963. He won Best of Show in the county hobby fair. (Photo courtesy of the Reading Eagle).

For the first 25 years of his working life, he was a small-town electrician in central Pennsylvania, and then, without even a bachelor’s degree himself, used his expertise in ship reconstruction to become a professor at Texas A&M University. Today, scores of his former students employ his methods worldwide.

The Egyptian model, though, hearkened to an earlier time, to the early years when my father still spent six days a week wiring factories and the wee hours of his nights building ship models in the basement.

Using what scant research he could find at the time about Egyptian shipbuilding, he attempted to reproduce with his model the original construction techniques. Each hull plank was about an inch and a half long, reflecting the short trees that the Egyptians used in shipbuilding. They were painstaking edge-joined, and the entire hull retained its shape from tension applied by a rope truss that ran from stem to stern. The Egyptians used no keels or frames.

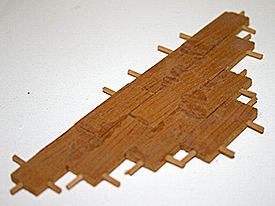

An example of the model’s joinery.

In all, the model had 2,000 pieces, and it took him more than 400 hours over 12 years to complete. As he built it, he began to lay the foundations of his new career, formulating the use of models in rebuilding sunken hulls.

In 1963, he arranged a meeting with George Bass, who had led the world’s first underwater archaeological dig off the coast of Turkey three years earlier. My father offered to build a model of a Byzantine wreck from the seventh century that Bass had uncovered. To seal the deal, to show his mettle as a modeler, he brought the Egyptian vessel with him to the meeting.

“I had no way of knowing how accurate it was or anything else,” Bass recalled. “It was the first time I’d ever looked at the model of an ancient ship. It wasn’t one of these slick yacht models.”

Nevertheless, Bass was thrilled with the idea of a Byzantine model, and this electrician seemed to know what he was doing. The two would begin a friendship and professional collaboration that would last the rest of their lives.

While my father would embark on one of the world’s more unusual career changes, the Egyptian model seemed to disappear.

No one, least of all my father, spent much time wondering what happened to it. He had little love for his models. Most weren’t built for aesthetics. He saw them as research tools that, once he had learned all he could from them, should be discarded. Because part of their lesson was to show how a ship broke apart when it sank, most didn’t last long. Only three others – including the one of the Byzantine wreck that he agreed to build for Bass – are known to have survived and are on display in museums in Cyprus, Turkey and South Carolina.

Perhaps that’s why I couldn’t get those letters out of my mind. Given the chance to find one of his long-lost works, I decided I had to know for sure what had become of the Egyptian ship. The letters provided a clue.

I got in touch with Cynthia Eiseman, a former student of Bass’s who’s been involved with nautical archaeology for decades. She wrote one of the letters in 1969, while working a summer job at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum. Her letter indicated my father had donated the Egyptian model to the museum, and she was asking what he wanted done with it.

The model soon after arriving at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum in 1965. Note the clay figures of the crew, which have since crumbled.

“It was a surprise to hear the model is still in existence as it was not built for display purposes and has led a hard life,” he wrote back. “I would like to see the model on my next trip to the museum to find out why it has not disintegrated because it is basically only held together by the pressure of its own gunwales.”

Eiseman, who still lives in Philadelphia, didn’t remember the exchange or the model, but she offered to help look for it.

A few days later, she called to say she’d found it. It had been sitting for years in the storeroom of the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia, which had been searching for a home for it.

The museum focuses on the maritime history of Philadelphia. Ancient Egyptian ships fall outside of its mandate, and the museum had “deaccessioned” the model in 1993. Since then, it remained in the a store room filled with shelves of ship models and seafaring artwork.

“Given that your dad never kept his models, it’s extraordinary that this one has survived,” Eiseman said.

Fortunately, the museum couldn’t bring itself to part with the ship.

“Museums sometimes have a hard time letting go,” Chief Curator Craig Bruns told me. “Nobody found a proper place for it until you asked. As a curator, I see it as a happy ending.”

Independence Seaport Museum Chief Curator Craig Bruns in the museum’s storeroom.

Last summer, I went to Philadelphia and drove the model to Texas, where it will but put on display in INA’s headquarters once a building renovation project is completed later this year.

Bruns provided letters from the museum’s files that filled in a few key details of the model’s history. My father wrote the museum in 1963 and offered to loan it the model, which he did in the summer of 1965.

While it didn’t fit with the museum’s mission, it was on display there for a time. Bruns gave me a plaque that had accompanied it and included the explanation: “While not a part of Delaware Valley history, it could be considered the `grandfather’ of all sea-going ships.”

It could also be considered the work that best represents my father’s transformation from hobbyist to ship expert.

The model remains in excellent condition. A few of the oars have fallen off and the crude figures my father fashioned to represent the crew have crumbled or broken away. The hull itself though, remains intact, still held to the proper curvature by the rope truss.

“It is an artifact of a discipline that he helped create,” INA President Deborah Carlson said. “As a teaching tool the model will be accessible to students and faculty leading seminars in ancient seafaring and ship construction technology.”

The hull was formed from one-and-half-inch pieces designed to recreate the short timbers used by Egyptian shipbuilders.

I wonder what my father, with his lack of sentiment for his creations, might say about that. He would be embarrassed by the model — there’s nothing that can be learned from it, he would say — yet if it benefited students, we would probably acquiesce to the display.

In the meantime, the Lost Ship Model waits to complete the last leg of its amazing journey. Sometimes, as I pass the room it’s in, I can’t help but stop there and peek inside its traveling crate. It’s as if my father’s dreams remain there, suspended in a time before they were fulfilled.

Nautical archaeology is now a recognized field of study, thanks to decades of effort by early pioneers like Bass and my father and the students they helped train. It is old enough that the field itself is developing its own history, a way for students who didn’t know the first generation to better understand how they developed their skills.

In a field that studies the past, the long-lost ship model offers a touchstone to its own unique history.

For more information about J. Richard Steffy see Loren Steffy’s book: The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

_______________________________________________

Loren Steffy is a columnist for the Houston Chronicle and the author of The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

* The opinions expressed by guest bloggers do not necessarily reflect those of the MUA, its staff, or its partner organizations.

Faced with imminent destruction, the junk will be saved. More than four years after I launched efforts to save the Free China, and nearly 57 years after his historic trans-Pacific crossing from Taiwan to San Francisco, the junk will make its return trip to Taiwan later this spring, where it will be preserved as an museum exhibit there, thanks to the Taiwan government. The junk– which is the oldest Chinese wooden sailing vessel and last of its kind in existence– will generate awareness of Chinese maritime achievement and culture and the Chinese diaspora. There are several unique aspects of this preservation project.

Faced with imminent destruction, the junk will be saved. More than four years after I launched efforts to save the Free China, and nearly 57 years after his historic trans-Pacific crossing from Taiwan to San Francisco, the junk will make its return trip to Taiwan later this spring, where it will be preserved as an museum exhibit there, thanks to the Taiwan government. The junk– which is the oldest Chinese wooden sailing vessel and last of its kind in existence– will generate awareness of Chinese maritime achievement and culture and the Chinese diaspora. There are several unique aspects of this preservation project.

El Centro Peruano de Arqueología Marítima y Subacuática (CPAMS), se formo a finales del año 2010 y esta formado actualmente por 4 miembros fundadores y una investigadora asociada, buscamos formar un equipo multidisciplinario aunque por el momento solo somos arqueólogos. El CPAMS tiene como objetivo promover la investigación científica arqueológica en ambientes marítimos subacuáticos, medios fluviales, lacustres, sus zonas terrestres de interacción así como el impacto del paisaje marítimo en el desarrollo de las sociedades a lo largo del tiempo. Buscamos difundir, proteger, preservar, conservar y poner en valor nuestro patrimonio natural y arqueológico distribuido en 2250 km del litoral pacífico, ríos, lagos costeros y de altura por medio de programas educativos para arqueólogos y talleres de sensibilización y desarrollo social.

El Centro Peruano de Arqueología Marítima y Subacuática (CPAMS), se formo a finales del año 2010 y esta formado actualmente por 4 miembros fundadores y una investigadora asociada, buscamos formar un equipo multidisciplinario aunque por el momento solo somos arqueólogos. El CPAMS tiene como objetivo promover la investigación científica arqueológica en ambientes marítimos subacuáticos, medios fluviales, lacustres, sus zonas terrestres de interacción así como el impacto del paisaje marítimo en el desarrollo de las sociedades a lo largo del tiempo. Buscamos difundir, proteger, preservar, conservar y poner en valor nuestro patrimonio natural y arqueológico distribuido en 2250 km del litoral pacífico, ríos, lagos costeros y de altura por medio de programas educativos para arqueólogos y talleres de sensibilización y desarrollo social. The Peruvian Centre for Maritime and Underwater Archaeology (CPAMS) was started at the end of 2010 and is currently made up of four founding members and an associate researcher. We intend to form a multidisciplinary team although at present we are still only archaeologists. The aim of the CPAMS is to promote scientific archaeological research in underwater maritime environments, rivers and lakes, their interaction areas on land as well as the impact that the maritime landscape has on society’s development over time. We seek to disseminate information on, protect, preserve, and conserve our natural and archaeological heritage that is distributed over the 2250km of the Pacific coastline, rivers, coastal and highland lakes and make it valued, by way of organizing educational programs for archaeologists as well as workshops on social development and awareness.

The Peruvian Centre for Maritime and Underwater Archaeology (CPAMS) was started at the end of 2010 and is currently made up of four founding members and an associate researcher. We intend to form a multidisciplinary team although at present we are still only archaeologists. The aim of the CPAMS is to promote scientific archaeological research in underwater maritime environments, rivers and lakes, their interaction areas on land as well as the impact that the maritime landscape has on society’s development over time. We seek to disseminate information on, protect, preserve, and conserve our natural and archaeological heritage that is distributed over the 2250km of the Pacific coastline, rivers, coastal and highland lakes and make it valued, by way of organizing educational programs for archaeologists as well as workshops on social development and awareness. I was fortunate enough to attend a UNESCO regional meeting on Underwater Cultural Heritage held in the magnificent Istanbul Archaeology Museum in October 2010. Of the eighteen nations from the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region that were formally represented, no less than fourteen (or nearly 80%) have ratified the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001). Another part of the world where there has been a very significant level of ratification has been Latin America and the Caribbean and one really important consequence of this has been the decline in official, state-supported, treasure hunting activities in these areas. On the other hand there are large areas of the world where very few countries have ratified the Convention – Northern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa and, sadly, my own region in Asia and the Pacific. Of the forty-eight nations included in the UNESCO region of Asia and the Pacific, for example, only two countries have ratified the Convention – Cambodia and Iran (or less than 5% of the countries in the region). There are, of course, many complex geo-political reasons why individual nations, or indeed whole regions, have failed to ratify this Convention in the nearly ten years since it was passed by UNESCO in late 2001. Some countries (like Australia) make much of the difficulties associated with federal nations trying to bring state and federal legislation into line with the provisions of the Convention and other countries claim to have issues with sovereignty and flagged vessels. I remain unconvinced by this kind of rhetoric and suspect that many countries are simply unwilling to expend funds in what is seen to be a relatively ‘unimportant’ area.

I was fortunate enough to attend a UNESCO regional meeting on Underwater Cultural Heritage held in the magnificent Istanbul Archaeology Museum in October 2010. Of the eighteen nations from the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region that were formally represented, no less than fourteen (or nearly 80%) have ratified the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001). Another part of the world where there has been a very significant level of ratification has been Latin America and the Caribbean and one really important consequence of this has been the decline in official, state-supported, treasure hunting activities in these areas. On the other hand there are large areas of the world where very few countries have ratified the Convention – Northern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa and, sadly, my own region in Asia and the Pacific. Of the forty-eight nations included in the UNESCO region of Asia and the Pacific, for example, only two countries have ratified the Convention – Cambodia and Iran (or less than 5% of the countries in the region). There are, of course, many complex geo-political reasons why individual nations, or indeed whole regions, have failed to ratify this Convention in the nearly ten years since it was passed by UNESCO in late 2001. Some countries (like Australia) make much of the difficulties associated with federal nations trying to bring state and federal legislation into line with the provisions of the Convention and other countries claim to have issues with sovereignty and flagged vessels. I remain unconvinced by this kind of rhetoric and suspect that many countries are simply unwilling to expend funds in what is seen to be a relatively ‘unimportant’ area.  I came to the field of maritime history like many of my colleagues did– serendipitously. My original area of expertise was in immigration and ethnicity, but when I was asked to teach a course in US Maritime History, I jumped at the chance: faced with a growing family and shrinking assets, it seemed like a good opportunity. Plus, how hard could it be: after all, most immigrants came to this nation via ship!

I came to the field of maritime history like many of my colleagues did– serendipitously. My original area of expertise was in immigration and ethnicity, but when I was asked to teach a course in US Maritime History, I jumped at the chance: faced with a growing family and shrinking assets, it seemed like a good opportunity. Plus, how hard could it be: after all, most immigrants came to this nation via ship! I recently attended the Society for Historical Archaeology’s Annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology in Austin, Texas. As a professional it’s easy to become focused on my niche within archaeology, but attending conferences like SHA always reminds me of the diversity of jobs available in the field. When I began studying archaeology, like most new students in the field, I recognized that jobs existed in universities and museums, but I didn’t realize just how many jobs were also available in the private sector. According to a 2005 survey conducted by the Society for American Archaeology, 34% of respondents indicated that they were employed in an academic setting, including full, assistant, visiting, or adjunct professors and research assistants and post-docs. The next largest employment sector identified was that of cultural resource management (CRM), which accounted for approximately 28% of the total (the full report is available online at

I recently attended the Society for Historical Archaeology’s Annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology in Austin, Texas. As a professional it’s easy to become focused on my niche within archaeology, but attending conferences like SHA always reminds me of the diversity of jobs available in the field. When I began studying archaeology, like most new students in the field, I recognized that jobs existed in universities and museums, but I didn’t realize just how many jobs were also available in the private sector. According to a 2005 survey conducted by the Society for American Archaeology, 34% of respondents indicated that they were employed in an academic setting, including full, assistant, visiting, or adjunct professors and research assistants and post-docs. The next largest employment sector identified was that of cultural resource management (CRM), which accounted for approximately 28% of the total (the full report is available online at  Avocationals can provide free, useful and valuable labor on field projects or on other work in direct support of projects. Although not trained to professional standards in archaeology, avocationals can bring a number of related or supplemental skills, including diving, boat handling, data management, equipment maintenance, forensics, and more. They also can assist in publication and outreach. The MUA hosts a number of posts from avocational groups.

Avocationals can provide free, useful and valuable labor on field projects or on other work in direct support of projects. Although not trained to professional standards in archaeology, avocationals can bring a number of related or supplemental skills, including diving, boat handling, data management, equipment maintenance, forensics, and more. They also can assist in publication and outreach. The MUA hosts a number of posts from avocational groups. The unfortunate events leading up to and following the Macondo well blowout, and the loss of eleven lives in April have focused international attention on the domestic oil and gas industry in the United States for the first time since the Exxon Valdez oil spill on March 24, 1989. In the 21 years since the Exxon Valdez disaster archaeologists have become more sophisticated in reacting to environmental and archaeological emergencies and in sharing that information with their colleagues. For the relatively small number of us who work in the oil and gas industry as underwater archaeologists the impact of the recent spill will be on our minds for years to come. Those of us who work offshore are highly aware of the innate dangers that surround offshore surveys, Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) operations, drilling operations, and infrastructure installation. I was offshore the day Macondo exploded and for those of us on the boat, our first concern was whether there was anything we could do to assist. Our second concern that day and the one we didn’t want to voice was whether we knew anyone aboard Deepwater Horizon.

The unfortunate events leading up to and following the Macondo well blowout, and the loss of eleven lives in April have focused international attention on the domestic oil and gas industry in the United States for the first time since the Exxon Valdez oil spill on March 24, 1989. In the 21 years since the Exxon Valdez disaster archaeologists have become more sophisticated in reacting to environmental and archaeological emergencies and in sharing that information with their colleagues. For the relatively small number of us who work in the oil and gas industry as underwater archaeologists the impact of the recent spill will be on our minds for years to come. Those of us who work offshore are highly aware of the innate dangers that surround offshore surveys, Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) operations, drilling operations, and infrastructure installation. I was offshore the day Macondo exploded and for those of us on the boat, our first concern was whether there was anything we could do to assist. Our second concern that day and the one we didn’t want to voice was whether we knew anyone aboard Deepwater Horizon. Throughout a thirty-year career in maritime archaeology, a particular hobby-horse of mine has been an element of good practice management that involves jointly sharing heritage responsibilities, as well as benefits and outcomes.

Throughout a thirty-year career in maritime archaeology, a particular hobby-horse of mine has been an element of good practice management that involves jointly sharing heritage responsibilities, as well as benefits and outcomes.